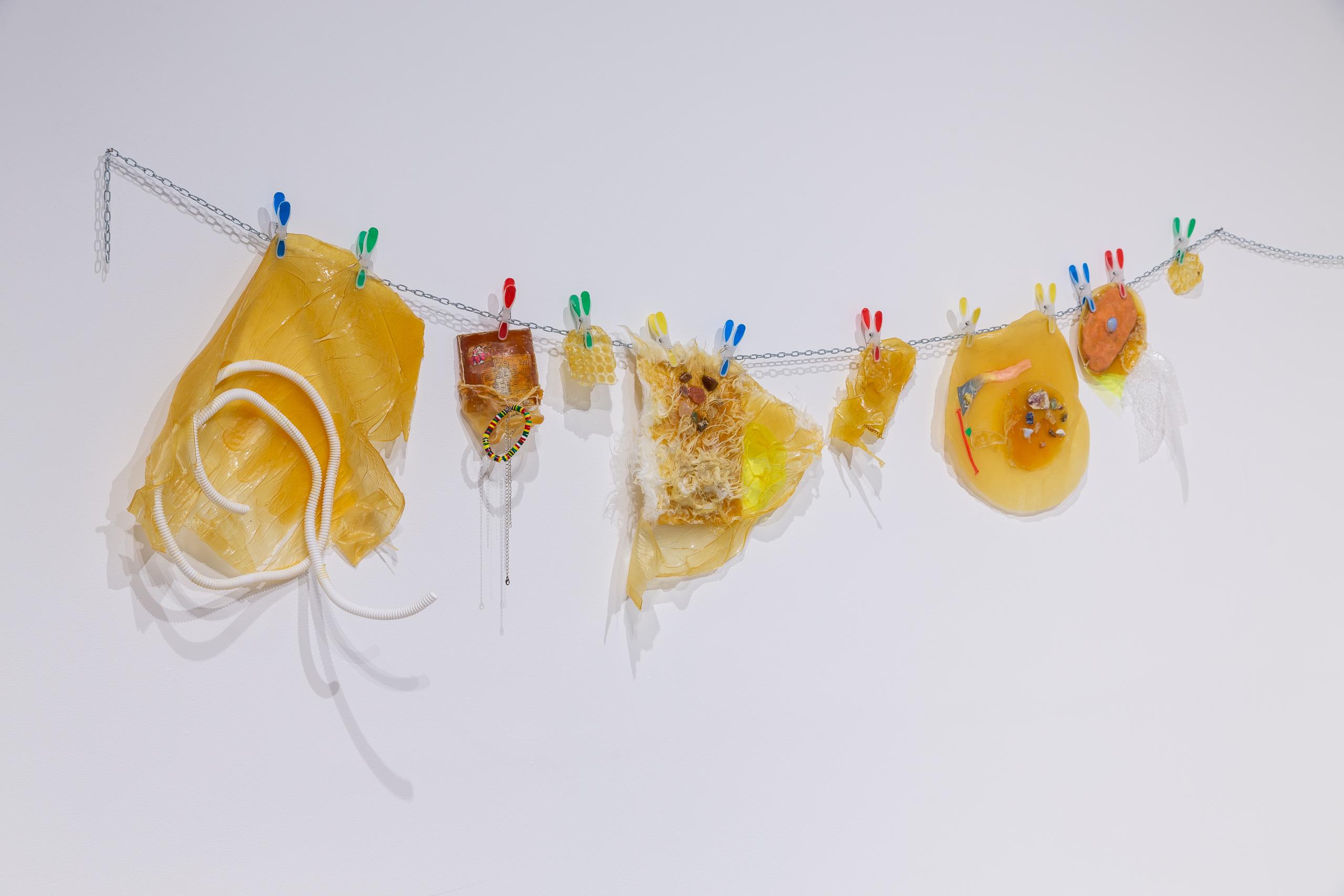

The works in A spill that stays streaming attempt to capture the moment when materials settle into one another, adapting to the often goopy, brittle, destructive or generative processes of matter moving and evolving. Working with the idea of “cooperative materiality”, these sculptures are my experiments with making materials work together to grow with or against their neighbours and surroundings. Using methods of squishing, stretching, spreading or sticking, my goal is to punctuate the life cycles of my materials with a little romance, like how a kid might smush their doll’s heads together to make it look like they’re kissing.

Exhibition photos by Scott Lee from SHOW.21 at Cambridge Art Galleries.

photo diary